The Old Malthouse

The Old Malthouse on St Johns Road is a unique Grade II listed building, with an extraordinary roof span covering the old drying room. When a developer proposed to convert it to multiple flats, the Society responded. At the time of writing (Summer 2020), the application has been refused and, thankfully, an application to refurbish the building as offices has subsequently been approved.

BCS Comment on the proposal to divide The Old Malthouse on St Johns Road into multiple flats.

17/02167/F and 17/02168/LB - The Old Malthouse St Johns Road Banbury - Conversion of building from B1(a) Offices to 25 residential flats, with ancillary parking, bin storage and amenity

In some ways the proposal seems to be a good one in terms of design and the conservation of the historic fabric of this very interesting Grade II-Listed Malthouse. That said, taking a Grade II Listed building of a type whose heritage significance largely derives from its large open floor spaces and irreversibly dividing it up into multiple domestic residential small units undoubtedly causes harm, although in terms of Paragraph 134 of the NPPF, in this case that harm would probably be regarded as ‘less than substantial harm’.

It is nevertheless a big step that needs thorough justification.

As noted in the NPPF, para 134 “Where a development proposal will lead to less than substantial harm to the significance of a designated heritage asset, this harm should be weighed against the public benefits of the proposal, including securing its optimum viable use. “

Guidance on “optimum viable use” is provided in the Government’s ‘Planning Practice Guide’

“What is a viable use for a heritage asset and how is it taken into account in planning decisions?”

“The vast majority of heritage assets are in private hands. Thus, sustaining heritage assets in the long term often requires an incentive for their active conservation. Putting heritage assets to a viable use is likely to lead to the investment in their maintenance necessary for their long-term conservation.

By their nature, some heritage assets have limited or even no economic end use. A scheduled monument in a rural area may preclude any use of the land other than as a pasture, whereas a listed building may potentially have a variety of alternative uses such as residential, commercial and leisure. In a small number of cases a heritage asset may be capable of active use in theory but be so important and sensitive to change that alterations to accommodate a viable use would lead to an unacceptable loss of significance. It is important that any use is viable, not just for the owner, but also the future conservation of the asset. It is obviously desirable to avoid successive harmful changes carried out in the interests of repeated speculative and failed uses.

If there is only one viable use, that use is the optimum viable use. If there is a range of alternative viable uses, the optimum use is the one likely to cause the least harm to the significance of the asset,not just through necessary initial changes, but also as a result of subsequent wear and tear and likely future changes.

The optimum viable use may not necessarily be the most profitable one...

Harmful development may sometimes be justified in the interests of realising the optimum viable use of an asset, notwithstanding the loss of significance caused provided the harm is minimised.”

Paragraph: 015 Reference ID: 18a-015-20140306

Revision date: 06 03 2014

Here we have a building that has functioned perfectly well, for many years, as up-to-date, open- plan, serviced offices. It would need little, or minimal change to continue in such a use if such a use remains viable.

To consent to a residential subdivision that will result in “less than substantial harm” the Council needs to assure itself that residential use is now the optimum viable future use for this building, rather than simply the one that is most profitable for the owner or developer. Thus the Council needs to be satisfied that the existing office use is now economically redundant and that there are no less damaging uses for the building that are less damaging. The only way to demonstrate redundancy is through appropriate marketing at an appropriate value.

Should the Council be content that multi-occupancy residential use is the only, or optimum viable use and that the proposal is the least harmful viable use, the council should aim to ensure that the development proposal minimises harm and that it “enhances or better reveals (the heritage) significance” of the asset (NPPF para 137) in order to compensate for any harm.

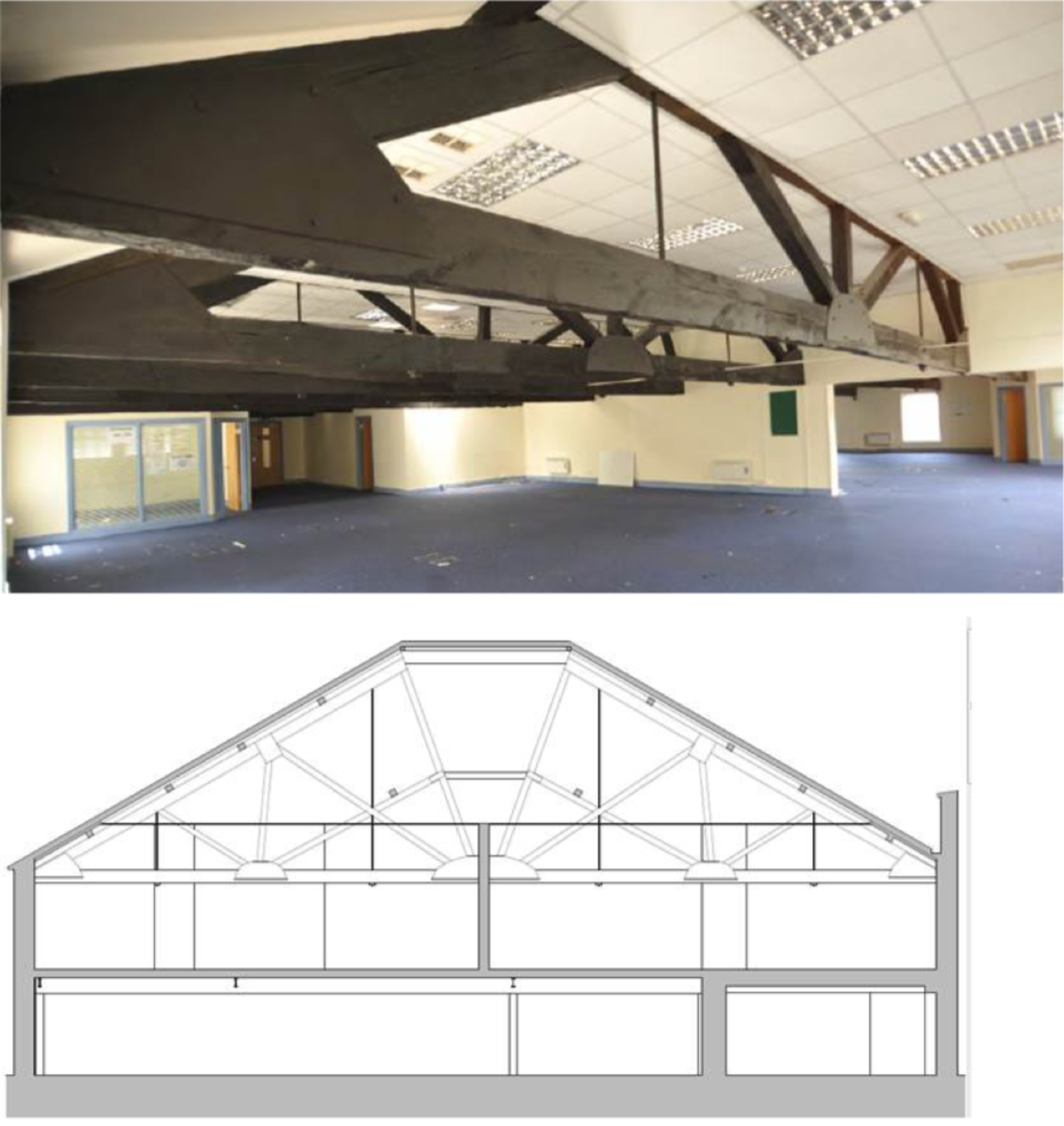

Of the many surviving malthouses of the late Georgian period, this Grade II malthouse is prodigious for its unusually wide floor-plan and its exceptionally ‘polite’ exterior treatment. The timber roof trusses that were provided to span this exceptionally wide-span building in 1834 (illustrated below) are indeed truly prodigious for their period and potentially of national significance in themselves. The roof structure certainly contributes outstandingly to the heritage significance of this Grade II listed malthouse and it certainly merits making more apparent in any development proposal for the building.

Here we are pleased with the developer’s proposed atrium, although we are concerned that this atrium will show only the central part of the roof trusses, rather than revealing their full structure across the whole width of the building.

We are also concerned at the absence of any detail design regarding of the flats themselves, so it remains uncertain if the roof trusses will remain visible within the flats, or whether the timberwork will need to be concealed within some, or all of them, on account of fire risk.

Whilst we are open to the idea of residential conversion of this very advanced and interesting building is the optimum viable use of this very unusaual and historic building, we would nevertheless seek the following:

1. Evidence of appropriate marketing to demonstrate the redundancy of the building as offices 2. Further detail of how the roof trusses will be made visible within the flats

3. Further exploration of the potential to enlarge the atrium so as to expose the full width and. height of at least three trusses, and

4. The securing through an appropriate condition of a detailed archaeological record of thebuilding to Historic England Level 3, with a Level 4 record of the roof structure.

We appreciate that 1), 2) and 3) may require that the application be temporarily withdrawn to allow for the provision of the required information and any necessary design changes.